The making of an architect (chapter 2)

What we were told on our first day at the Versailles school of architecture. Learning to draw complex architectural drawings the hard way and my first encounter with blatant anti-semitism.

They gathered all the new students in the large amphitheater called "La Rotonde." I didn’t understand why so many older students were also gathering, standing at the back, smiling and whispering. Almost the entire teaching staff stood in a long line. They were all dressed in black from head to toe. Then one of them, the oldest, called Guillemin, took the microphone and, without any unnecessary preamble, simply began to speak:

"Architecture is the most beautiful profession in the world but also one of the most ungrateful. The good news for you, and for the profession, is that most of those sitting here in the amphitheater will not become architects. Most of you will be really bad, and we will fail you again and again with joy. We will make your lives miserable. We will pile on more and more work so you won’t be able to sleep if you try to keep up with all the tasks. A large part of you can’t even think in three dimensions, and life for those, especially, will be hell on earth. Most of you are incapable of creating anything or being creative. Certainly not under pressure. Just because you got good high school grades and managed to get into Versailles means nothing. Absolutely nothing. You know nothing about architecture, you don’t know what it involves, and most of you won’t learn anything either. Half of you today are females, but this profession is still completely male-dominated. There are 130 of you today, and if 30 of you get a diploma, statistically, only 5 or 6 of them will be women, and their lives on construction sites will be a continuous nightmare throughout their careers, if they even make it to the construction sites. Those of you who do graduate will have to work very hard until the age of 40, and only then will you be considered 'young architects' who understand a little of what they are doing. Also, don’t expect to make money before that age. Anyone who wants money should get up now and go study finance at HEC, you probably already have the grades necessary, only the preparatory course is missing.

Most of those who do become architects from here will be mediocre to terrible. When you leave here, you will know only a little less nothing beyond the nothing you know now. It takes decades to build a good architect; no one becomes a worthy architect after seven years of sitting on their arses in lectures and cutting hundreds of cardboard models. Forget it. The quality of an architect is a function of how much culture has entered them, how much they have absorbed, how much they have learned and experienced. Architecture is more experienced than taught. It will take you years to properly read and understand a plan and comprehend how every room and space feels just from the black lines on it. It will take you even longer to translate future emotions and experiences of people you will never meet or know into future living space.

An architect is a supreme planner. You need to know how to design everything. Not just houses. Everything. From a fork to a city and even beyond that if asked. Aristotle said that 'architecture is the mother of all arts,' but I tell you it’s much more than that. You will never be good architects if you don’t understand people, if you don’t understand what they want even without them telling you. It’s not enough to know how to draw, it’s not enough to know how to plan; you also need to know how to observe. To read what is not written, to listen to what has not yet been said, and to understand the silence of the carved stones and the tensioned concrete, to follow the play of light and shadow and understand how the winter sun sends its long arms through the windows to places where the summer sun will never reach.

Today, you stand at the great gates of architecture. Our profession is ancient, we were the first to provide real shelter, those who brought humanity out of the darkness of cold caves and their shadows into the air and sunlight. Give me wooden beams and stones, and I will build you a shelter with my old hands. Because the architect must also know where every nail is nailed and how to nail it. If you think you won’t have to clean concrete from under your delicate fingernails, you are wrong. We have courtyards here and building materials, and here we understand the material through touch. You need to know the weight of a brick, its dimensions. How it is placed in England and how in France. You need to know what will hold and what will fall, and with one look understand what is wrong with what you see. Or alternatively, recognize rare genius. Know when to demand the dismantling of a wall just built because it deviates by one centimeter from what you specified in the plan. Your plan is the law, it is your contract with the client, it is your shield against the authorities. You are called 'Master of the Work' (Maîtres d’œuvre - the official title for the planning architect in France) because that’s what you will be. You will be masters of the creation. The creation will twist and turn and ultimately obey your commands. The creation wants to be free, and you imprison it in the fetters of this world. You subjugate it to the laws of physics and nature, and for that, you will also receive your meager reward.

The profession you seek to acquire is awe-inspiring. Sacred. Grueling. While every other profession starts from a broad base and as the years go by, people specialize in an increasingly narrow field, you will do the exact opposite. You will start small and expand more and more. An architect is a generalist by definition, not a specialist. You will know a little about everything and not a lot about one thing. In six, seven, or eight years, a few dozen of you will join us and call us 'tu’ and not ‘vous’. You will have to accept our ethical and moral rules and become our younger brothers in the profession. But until then, there is a long and arduous road ahead. Good luck to you all."

The amphitheater was completely silent throughout the speech. Beyond Guillemin's voice, only the scratching of pens on folio pages was heard. No whispers or talking. The older students began to leave slowly while a lecturer named Nathalie took the microphone and started a series of administrative announcements. One student was called to distribute the schedule, and it quickly became clear to everyone that it was no less than 40 hours of weekly study. Every day, Monday to Friday, from 8:30 to 16:30. The subjects were varied – from the expected, such as construction (statics and material strength) and "project," which is proper architectural work, to classes in the history of ancient architecture, history of contemporary architecture, art history, anthropology, urban geography, plastic arts, architectural analysis, and more.

After Nathalie's words, it was the turn of three students, namely two male students and one female student. They said they were representatives of the school's "ateliers" (workshops), and they invited us to tour them immediately after lunch.

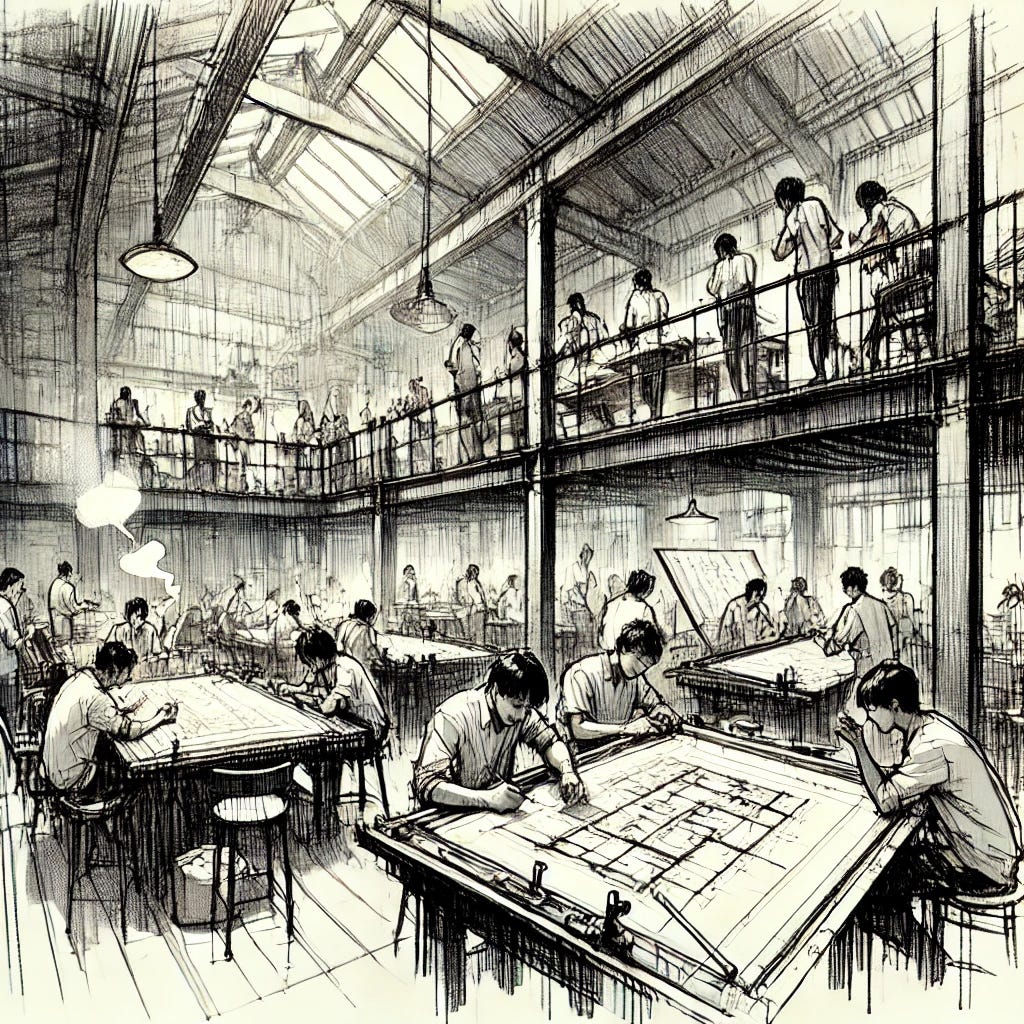

The ateliers are the heart of architecture schools. In all other french schools, it was customary to have as many ateliers as project lecturers. You would have joined the atelier of the lecturer who would teach you. and you would have been allowed in only on certain times and certain conditions. In Versailles however, the system was entirely different: two large, enormous workshops each with a large mezzanine that basically would double the available space, as the ceilings were so high. they were called: Atelier 13 – aka “les fachos” ("the fascists") and Atelier 14. there was one smaller, with no mezzanine called Atelier 19, set in the school's giant attic – the atelier of "the nerds." There was a sort of covert rivalry between all of them, and each had a mix of all the years from first year to those working on their final project. This was Versailles' huge advantage over other schools. The autonomy of each of these ateliers. Generally speaking, few who did not belong to one of the ateliers finished as architects. Their added value was enormous.

After the tour, I chose to join atelier 14. Its vibe seemed more suitable to me somehow.

All the first-year newcomers – i.e - us – were gathered at the center of the atelier. Completely “unarchitecturally”, it was in the shape of a somewhat amorphous triangle made of desks and lockers. All set around a massive raw concrete column. We were given a few drafting tables with built-in rulers and some tables for building cardboard models, and that was it.

One of the older students climbed onto one of the tables and explained the rules. From now on, we were called "les nouveaux" (the new ones), and we were essentially the apprentices here. Errand runners. We could only sit in this newcomers' triangle called "Triangle des Nouveaux," and we were allowed to wander around the atelier and enter corners only by invitation. Woe to anyone who touches a project of the more advanced years. Woe to anyone who’s noisy or loud. If we wanted to listen to the radio, it was either FIP or TSF Jazz, or Radio Nova, and we had to check which radio was playing among the older students and synchronize with it. There were a few stereo systems among the older students, and sometimes they would ask to turn off the radio, and someone would play hours and hours of Bach or Rachmaninoff. Those who behaved well and helped the older students with various tasks would get "corrections" – usually a third-year student and above who would kindly sit with you on your projects and explain where you were being foolish with your poor attempts at architectural planning and what you would fail on. In practice, those who got the most corrections, regardless of how much they helped around, were, of course, the beauties of the year who quickly learned which older student to reject and when. Male students had to give a certain number of hours of work per week on other people's projects to get their own projects looked at.

You had to know who to work for to get significant help and who to ignore elegantly when they were asking for help. It was tough, but through this extra work, you learned a lot. Regardless of your personal projects. There was quite a bit of politics in the atelier, intrigues. Love triangles and ex-couples who didn't speak to each other. There were clans. There was a very intimate part of the atelier called "the Bronx," where the "heavyweights" (those who dragged their time in advanced years and delayed their final project) sat. They were sometimes doing some serious drugs there. Including the scary-foam-at-the-mouth kinds at times. There was a ‘chill’ area, complete with a varied alcohol bar. And a film projector that usually showed old porn movies or Godzilla or various Eastern European crap by Bela Tarr, Tarkovsky, or old Eisenstein and communist propaganda films. Some of them kind of "lived" there, sleeping whole nights at times - without going home.

A permanent cloud of cigarette, tobacco, and marijuana smoke hovered over the atelier. Constantly. You couldn’t help but smoke. Your eyes, already red from lack of sleep, turned even redder. Very quickly, I learned to do like everyone else – to stick the cigarette at the corner of my mouth so that both my hands were free, and I could draw without taking it out until it was finished and without ashing. Who has time for ashing?

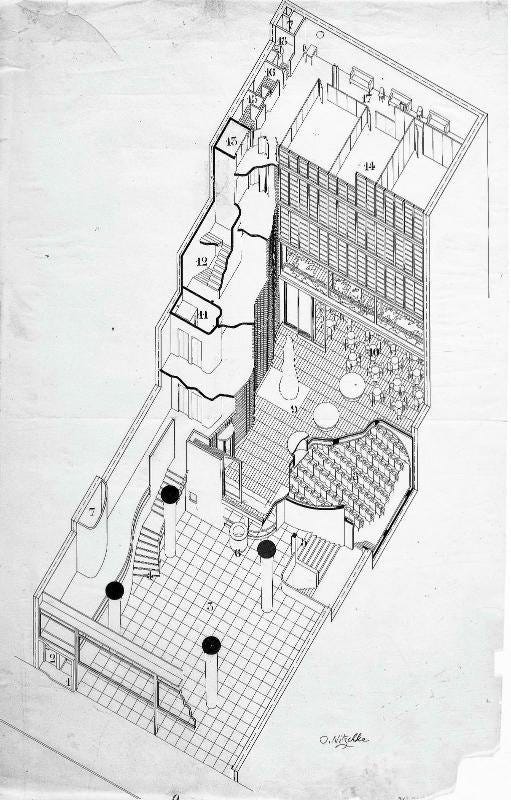

The days were very long, and the nights even longer. Right from the start. I remember the very first project we got in construction was to find a piece of furniture and do an "exploded axonometric," a kind of three-dimensional drawing a bit like IKEA assembly instructions that show where every screw goes. I chose a folding chair I had in my rented apartment but couldn’t figure out how to build this axonometric drawing. We hadn’t yet learned the drawing rules at all. So I worked for 3-4 hours for this third-year girl named Liza, and in return, she showed me how to do it – first, you draw a horizontal line. And you mark its midpoint. On this point, you place the tip of your set square and draw a line at a 30-degree angle from the horizontal line, then you flip the set square and draw a line at a 60-degree angle. Between these two lines, you draw the chair's plan in two dimensions and extend vertical lines from it that create the illusion of three dimensions (see attached example – not my drawing). This was the first time in my life, after all of elementary and high school, that I understood what this ruler was for.

There was no way of learning this technique except from an older student in one of those ateliers. Most of those who chose to work from home got a failing grade because they couldn’t create a proper axonometric drawing. I quickly realized that much of what you learn, you "learn from the heap," as the French say. That is, you manage on your own. The lecturers don’t care that you don’t yet master any technique; they demand results, and it was a real survival war because if you failed in more than two subjects (score less than 10) at the end of the year, you had two options – either repeat the entire year or drop out. Most dropped out. I got 14/20 on my exploded axonometric chair and was really bummed because there was nothing inaccurate or wrong. Why did I get only "70/100"??? I came all bummed out to Liza and showed her the grade. She laughed at me and said, "Idiot, I wish I got 14 in construction, it’s a very good grade. You’re not only new, but you’re also a funny Jew. You always want more than they give, huh?" Oh yes. Liza was quite an anti-Semite, and she wasn’t the only one.

So where are Chapters 3-10?